Vogue February 2002

Nostalgia, by Alison Rose

Kathy Carpenter was one of a handful of gorgeous girls whose faces and bodies were all over the pages of fashion magazines in the mid-sixties. If you wanted to see Kathy Carpenter in a photograph, she was right there at a newsstand, often on a cover, a reliable image. Obviously there was Twiggy, and there was Veruschka, but they were from Europe. Kathy Carpenter was American, more kindred. I was kind of in that world, sort of, but since I didn't know what world, if any, I wanted to be part of, I preferred to stay in my apartment at 220 East Fifty-seventh Street doing nothing or looking over contact sheets from sittings with Duane Michals, or Arthur Elgort. I was in a hair ad, with a gathering of many fairly great beauties from Sweden and Germany. But when Kathy Carpenter began living in the building, it was startling. I would see her come and go. She was flawlessly well dressed, as if where she was going was the best place to be, even if it was just to the grocery store around the corner. She had the good manners to say good morning if we happened to be in the elevator at the same time, but I never had the nerve to say anything more.

Kathy Carpenter was in the laundry room in the basement. I was there, too. It was an evening in the spring around 1966 when I got an impulse. She was taking her things out of the washing machine and putting them in the dryer. She did it quickly and left the laundry room. I heard the elevator doors open and shut. I don't remember what she was wearing. Often it was difficult to look at her because she was a fairy tale in my head. I went upstairs myself a few minutes later. When I came back down my laundry was dry, and I was alone. I had finished stuffing my towels into a laundry bag when it occurred to me that her dryer had not completed its cycle.

The drum of the dryer is revolving furiously. I pull open the door. The drum gradually slows, and the clothes come to rest. Rummaging through the hot clothes looking for a likely item -- that's what I am doing. I do this fast, because I might get caught. I latch on to something small, not a washcloth, put it in my bag, and retreat to my apartment.

Upstairs, my roommate, Francine, in a long black dinner dress, was sitting on the edge of one twin bed putting on pale fishnet stockings. I took Kathy Carpenter's piece of laundry from my laundry bag. It turned out to be an article of thin white cotton lingerie, white eyelet around the edges. I laid it on the bed and told Francine that I had removed the cotton thing from Kathy Carpenter's clothes dryer. Francine's disapproval showed first in the way she lowered her eyes, pointedly not looking at the evidence. Then she said, "Oh, Alison, now look what you've done," as if wholeheartedly giving up on me. Then she put on her black grosgrain pumps, picked up her black clutch, and went out to meet her date.

After the apartment door shut, I stood in front of the full-length standing mirror and held up the clean white thing -- it was still warm -- in front of my clothes. There I was behind it: myself. Catastrophic as the clothes dryer incident may have been, I now had a tangible talisman of normalcy and steadiness instead of just the idea of being a girl other than myself. It was one of those times when envy doesn't feel like envy.

I never tried it on, or thought about trying on this piece of Kathy Carpenter's lingerie. It was Kathy Carpenter's. I folded it in quarters ceremoniously; then I tucked it away in my top left dresser drawer. Carefully. My underwear was strewn around in there, but Kathy Carpenter's washed white eyelet talisman had a place all to itself, in a corner in the back of the drawer.

When I think of Kathy Carpenter in the pages of fashion magazines in the sixties, I see her in bathing suits; she's robust, vigorous, rangy, as pretty as a girl could be without overdoing it. Let me say this: I don't thing she made too big a deal out of her prettiness. She wasn't starry or self-conscious or mean or nervous or vacant or vain, either in the photographs or in the 220 East Fifty-seventh Street lobby, where her face never, not once, looked anguished or on the verge of any bad thoughts, and she seemed to have a good disposition. She not only seemed free of fragmentation, she seemed like a regular girl. This is why it helped to have something that belonged to her.

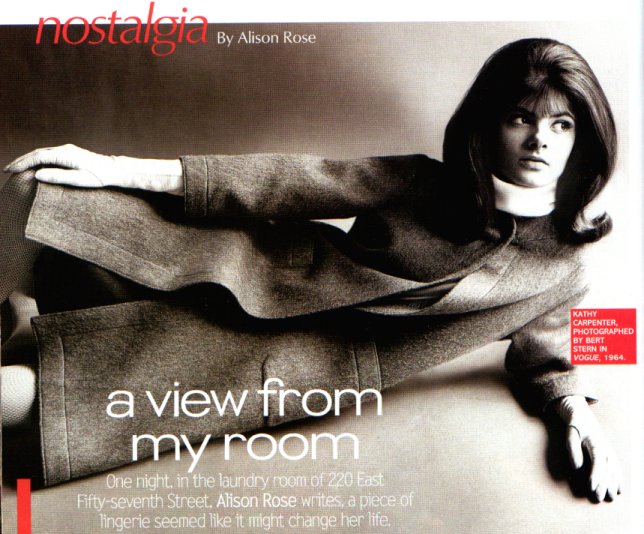

In this photograph that Bert Stern took of Kathy Carpenter for Vogue, she has glossy, dark-brown, below-the-shoulders hair and long bangs, and looks like a Miss Porter's girl, because she was. Her looks are straightforward, mostly unintimidating: beguiling, not fierce beauty. She has a big face, a square jaw, and uptilted nose, not full lips. She is wearing whitish-pink lipstick. Kathy Carpenter's whole countenance said it was all-American without being blonde. This is precisely what she looked like when we lived in the same building.

It wasn't as if there hadn't been photographs of me in magazines. That wasn't the point at all. There as a good one in Seventeen: a pink-and-gray-paisley dress with a matching kerchief for Jonathan Logan. My long bangs looked just like Kathy Carpenter's long bangs did coming out of the polka-dot kerchief that I saw her wearing in a magazine. I had that whitish-pink lipstick on, too. I was in a bicycle shop, propped against many bicycles jammed together all around me. The photograph has a particular melancholic charm -- everyone said so -- but I do not look robust, vigorous, or rangy, or appear to have a good disposition.

I had also been sent to see Richard Avedon. I had on a pink-linen V-neck sleeveless dress. Avedon sent me right away to Vogue, in the Graybar Building, to see Diana Vreeland, who had me try on a black cocktail dress. I stood on one of those step-up platforms in front of a mirror while Mrs. Vreeland, also dressed in black, looked at me and the dress but didn't say anything. Another woman got down on her knees on the platform to do some pinning. Later that day, the woman in Avedon's studio made the booking -- for four pages in Vogue. The rest of the story gets sad: the plan fell through. The sadness informs me that I would still give anything to have been Kathy Carpenter, or at least who I imagined her to be.

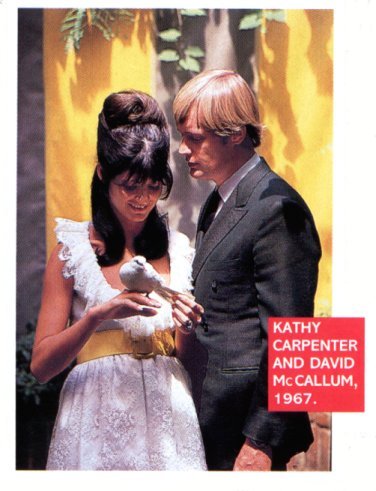

I sometimes saw

her in the elevator or in the lobby with a man who had the silkiest straight

blond hair, and he turned out to be David McCallum -- Illya, from The Man

From U.N.C.L.E. Francine told me she'd seen them walking on the street.

She said they both moved in the same way, as if synchronized. A photograph of

Kathy Carpenter and David McCallum that ran in Glamour has her in a white

lacy dress with a wide yellow belt, a dove sitting on one hand, it's tail in

the other hand. David McCallum's silky hair is ever-so-blond. His face looks

as if he loves her. It was not a stupid photograph of fake love but of love

itself, whatever that is. Certainly of devotion.

I sometimes saw

her in the elevator or in the lobby with a man who had the silkiest straight

blond hair, and he turned out to be David McCallum -- Illya, from The Man

From U.N.C.L.E. Francine told me she'd seen them walking on the street.

She said they both moved in the same way, as if synchronized. A photograph of

Kathy Carpenter and David McCallum that ran in Glamour has her in a white

lacy dress with a wide yellow belt, a dove sitting on one hand, it's tail in

the other hand. David McCallum's silky hair is ever-so-blond. His face looks

as if he loves her. It was not a stupid photograph of fake love but of love

itself, whatever that is. Certainly of devotion.

I hadn't thought of Kathy Carpenter or her eyelet lingerie in a year or more -- she'd moved out of the building -- when the man I was living with in that same apartment showed me her wedding photograph in the Times. It was 1967. Kathy Carpenter had married David McCallum. She looked impeccably bride-like, of course, all in white, with a white lacy mantilla over her dark hair. I cut the photograph out of the newspaper and put it underneath the still neatly folded packet in the back of my dresser drawer. I never looked at either of these things, but I knew they were there. Sometime later, I saw her in a long, navy-blue cashmere coat pushing one of those huge, dark baby carriages from England up Park Avenue. Even though it's true that I have done other things, Kathy Carpenter did everything I never did. This is not a complaint, it's a fact.

In the early nineties, I went as a reporter to an alumnae party for Miss Porter's School. I was interviewing when I saw Kathy Carpenter and David McCallum across the room. There she was, her regular, real, non-blonde American prettiness more definitely grown-up. She was wearing a tailored green suit. McCallum was looking at his wife's face the way he had in the photograph with the dove: devoted. They were separate from the crowd.

I was nervous getting over to their side of the room, but I did it. I said I had lived at 220 East Fifty-seventh Street when she lived there. When I told them with giddy embarrassment but authoritatively that Kathy had been my ideal of glorious perfection and normalcy, they both laughed,but not madly, not as if I had been irrevocably wrong. Then, all in a moment, David McCallum, who still had all his silky blond hair, looked so sad it seemed as if he might cry. Then he did, for a split second. He apologized and said something about youth, and that his father had recently died. Kathy, who was taller, put one of her long arms around his shoulder and kept it there. Of course I didn't tell them about my theft from the hot dryer in the basement, or the newspaper clipping of Kathy as a bride, or that my mother had thrown both artifacts away when she came to New York to clear out my apartment in 1970. (I had moved to Los Angeles.) Losing them hadn't mattered all that much. I have Kathy Carpenter's face and whatever it was she meant to me inside my head, where no one can ever throw it out, so that I'll never be rid of it lose it.