From Motion Picture magazine

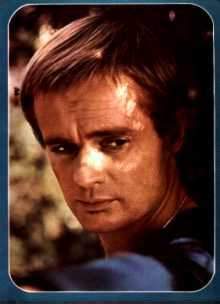

In these times ... when the U.S. is being blasted on every side, it's refreshing to hear a forthright young Englishman, David McCallum, proudly tell the world:

Three years ago this month, a fair-haired Scot landed at New York's International Airport to catch a plane for Hollywood. He was a successful actor in English films and without trying to throw his weight around, he did explain to the customs man, "Excuse me, but I'm in a hurry, I have a plane to catch."

The customs man just looked him calmly in the eye and answered, "Everybody's got a plane to catch, buddy. That's life."

The actor missed his plane, but far from being piqued, he was frankly enchanted with the attitude of this New York customs official, the first American he'd met over here; and as he tried to make his way around the vast airport by taxi, he became even more intrigued with the attitude and the conversation of New York cabbies. The terminal he wanted was less than a block away but to the left, and the only possible way to circle the place was to the right. Before any of them agreed to do it at all, at least four of them calculated the taxi fare, and each said frankly he'd rather snag a customer going into Manhattan, and run up a decent fare. This was the American way, the Scotsman decided. There were no class differences to worry about - he liked that. There were no pretenses flying about. The American attitude was damned basic, and each man stood on his own feet and expressed himself graphically. Indeed, self-expression seemed to be a national institution.

Today, one movie and thirty television episodes later, Mr. McCallum is himself an American institution. The fair-haired man from

U.N.C.L.E. has something about his sensitive face and shy-but-daring manner which has captivated the entire country. This year's "I Am

An American Day Parade" in Baltimore had David as grand marshal, and why not? He's bought a house in the Hollywood Hills; he's

traveled in almost every state on promotional tours, and he's just back from Miami, where he not only explored underwater for Around

the World Under the Sea, but also did some exploring into some extraordinary American folk customs. And one of the most ardent

voices cheering for the Dodgers belongs to this Scot who never saw a baseball game until now!

"I've asked my manager to get me my first papers to become an American citizen," David told me when we met for lunch at the MGM commissary. "There's no hurry because you have to be here for five years. But so far as countries are concerned, I don't go to a place to see what's there, but who is there. I think your life is governed not by the bricks or mortar around you, it's governed by who holds your hand and who spits in your eye. We have now lived the past three years in America, in California, and lots of people have spat in my eye and a few have held my hand. I think that a person who lives in whatever country should feel a certain obligation to that country, as they are governed by its laws. I feel it's a person's duty to participate in the governing of the country in which he lives.

"My family is my real reason for staying. If I had no family, my wife and I would lead a much more romantic and nomadic existence. We'd be going back and forth to London all the time and working all over the world. But when you have children that get to school age (Paul is 7, Jason, 3 and Valentine, 2), your parental instincts take over and you settle down. We've settled ..."

Interestingly enough, the West - land of cowboys - was what America meant to David before he got here. "I've always loved to see westerns, the pictures with the eternally romantic story, the ultimate dramatic delineation of good guys and bad guys. Some of my favorite western actors were Gary Cooper, Henry Fonda, John Wayne, Jean Arthur (he always mentions Jean Arthur, no matter what the category), Jimmy Stewart, Errol Flynn, and They Died With Their Boots On."

He grinned, and I wish I could have snapped a picture, because this was not the Illya face, as David was sporting a three day growth of grizzled beard for the horseback chase sequence in U.N.C.L.E. being filmed that afternoon. David is going to love this. He learned to ride in Australia, making a picture there in 1957. "We went on a sheep farm and there was a wrangler about my age; he thought me absolutely crazy when I said I wanted to learn to ride. 'You don't learn, you ride,' he told me. We rode for nine hours that first day. I was bowlegged for three days." Now, of course, he rides well and, of course, swims like a fish underwater, something he's not just learned for the new picture but has done all his life.

As a lad in England, he went to various schools because during the war the McCallums were constantly being evacuated. They lived here and there and he attended schools comparable to our public schools, finally ending up at UCS in London, which is a public school comparable to our private schools.

He loved swimming, and had a bicycle, which he used to go everywhere. "This is one big difference between America and England. Teenagers in England have bicycles; I've never know a teenager there to have a car - even in a university, only a few students have cars." David was a fair student, one whose report cards always carried the message "Does well, but could do better."

He played cricket only rarely, and when he did, they always put him out in what we'd call center field in baseball. Way out there, young David would look at the sky and dream, and when the ball came his way, his teammates would have to let out a shriek to waken him. "Depending on how fast they wakened me, I would or would not catch the ball."

But when he came to America, David was interested in seeing American sports. He was able to understand football easily, but at his first game he became to fascinated with the audience he scarcely watched the play. The middle-aged lady next to him, obviously a football widow, was sound asleep, while her husband jumped up and down pounding his huge hands together like a rock crusher and screaming at the top of his voice. Then suddenly the man stopped abruptly like a machine that had run down. He dropped to his seat and jabbed the poor snoring lady in the ribs. "I'm thirsty," he said. The woman never asked the man what he wanted. She just struggled to her feet, and ten minutes later re-appeared with a hot dog and a cup of hot coffee. The man took the sandwich and the cup, and the next instant jumped to his feet again and started shouting, but because of the food, he couldn't pound his hands. So he woke his wife again, handed her the sandwich and the cup, and went on pounding.

To this day, that's American football to David.

But baseball is something else again. Charles Bronson (you saw him in The Sandpiper) took David to watch the Dodgers play another team "which shall remain anonymous because it was a devastating defeat ... but it was a great, great game and I was an instant convert." He's been a steady rooter at Chavez Ravine ever since.

And he's learned to fish. His uncle, John Abercromby, used to take him fishing when he was a boy in Scotland and tried to teach him to use the fly lure, but David lost so many flies on the trees behind him that Uncle John gave up. Keenan Wynn's ex-brother-in-law lives in Miami, and once while they were there filming, Keenan, Art and David used to go out in Art's boat. The first day, David spent six straight hours casting. He became as brown as a Seminole Indian and caught barracuda, snapper and white jack.

Some of the shooting for the film was sometimes done in the ocean down toward the Florida Keys. When they weren't on location, there was a big hole in the studio floor with a hatch over it. They would pour David into a huge make-shift-science-fiction suit, and it was so heavy that the minute they let him down he dropped to the bottom where he stayed throughout he shot. "Then you hoped they'd pull you back up. I said to the prop man, 'It's not so bad down there, it's the only place you can get away from all the noise.' But I'd hope no one would goof."

He grinned when he said it, because this is strictly "Americanese" which has rubbed off. "I had to buy Webster's in defense," he says. "I've always been interested in the origin of words. I studies Latin and Greek about eight years, and this gives one a pretty good basis for most derivations. However, there are so many words from the American frontier, words straight out of wagon trains, and they all have a reason. Talk to an Englishman about jerky, he couldn't possibly know what you meant."

David has not only been boning up on the West and on word derivations and folklore, in Florida he looked up the man who takes venom from snakes. This is a Mr. Haas, who has worked with the serpents for years, has been bitten a number of times, almost lost his life, and is now virtually immune. David was fascinated at the manner in which the man whips the snakes out of their cages, grabs them by the back of the head so they can't twist and bite him, then allows them to bit a diaphragm over a glass. The snakes bite viciously and the venom runs out of their mouths down the side of a jar. "I wanted to take Paul along, but there's such viciousness, I thought it might be too traumatic an experience."

He drove down the romantic Tamiami Trail, and visited an Indian village, developed a healthy respect for porpoises (Flipper has such intelligence), brought a two-foot shell back from the bottom of the sea ...Jill's going to make a centerpiece of that. And wherever he goes, he rents a car and explores the area. "I've followed the Mormon trail, and when you look over the cliffs where they used to lower the wagons and then drag them up the other side, you see the graves of the children and others who didn't make it. You realize that the West was won - not just come across! It was dragged out of the dirt and the men fought for it with great energy. The right of an American to carry a gun is a sort of symbol which comes from that time. In a few hundred years you have achieved in America what it took thousands of years to achieve in Europe. Mind, you borrowed some things, but the American way of life has a different pulse, the pulse of what's going on. I like that."

Another sign that America's rubbed off on David - "I don't find so many holes in my trouser pockets which I got from carrying that English money around. I don't carry a dime." He shows me his wallet, and its only contents are a string of credit cards which are of value when he can find his wallet. But the fact is, he loses it as often as five times a day.

In England, David explains, when you are old enough and earning sufficient salary, you open a bank account. This necessitates meeting your bank manager, and you have to be pretty intrepid to enter his office because this is the man who controls everything. You deposit your twenty-five pounds and you get a checkbook. The banks of England make their money from lending money and from overdrafts: so as your bank manager comes to trust you, he eventually allows you to draw an overdraft. It means that from then on, you start living on a sort of credit basis. Result: "From the day I opened my first account until I left the United Kingdom, I was in a hopeless mess.

"However, in London I had a bank manager, a Mr. Silburn, who did more to help my career than anyone else. He allowed me an overdraft so I could pick and choose my parts. He'd seen me on television, but whether he gave me such leeway because he felt I could make it, I don't know. He was a gentleman in the best sense of the word."

"I don't think our family life, our basic life, has changed because of coming to America. I don't believe in setting up barriers between people because they're born in this place or that and have this or that allegiance. The minute you do, you set up an element of competition between people, and the my-way-is-better-than-your-way attitude results, inevitably, in some form of friction or aggression. And who needs it? We should learn to live and love our neighbors as ourselves for the sake of peace and progress. Inherent in every human being, however, particularly the male, there is a desire to fight, to be aggressive. But in some cases it is accented by training. In the Army, for instance, I had a mad instructor who was from the parachute troops. He was a captain - and a lunatic! The great moment in his life was when he finally stood face to face with an enemy. They were no more than two feet apart. Both fired their submachine guns point blank at the other. Both guns jammed. The captain took his gun and threw it with all his strength at the other man. The other man took a grenade and flung it at the captain. The grenade hit him on the side of the face, he lost an eye and had a great scar seared across his head. But he'd thrown his gun with such force that the other man was killed. And this was the great moment, the moment he will always "proudly" remember.

I've always said that a section of the world should be put aside for fighting. It should have a red army and a blue army; then anyone who feels like releasing his aggressions could join one of these armies and help fight the other army!

"I heard Billy Graham once say that until everybody lives with an awareness of the needs of the people in his immediate proximity ... his family, his neighbors, his fellow citizens ... only then can you achieve any form of stability or peace. It's a twenty-four-hour-a-day task, a twenty-four-hour-a-day obligation."

That's the kind of Americanization David McCallum has in mind. That's the way of life in which he hopes to raise his sons.

- By Jane Ardmore