The

Mystic Cult of Millions

The

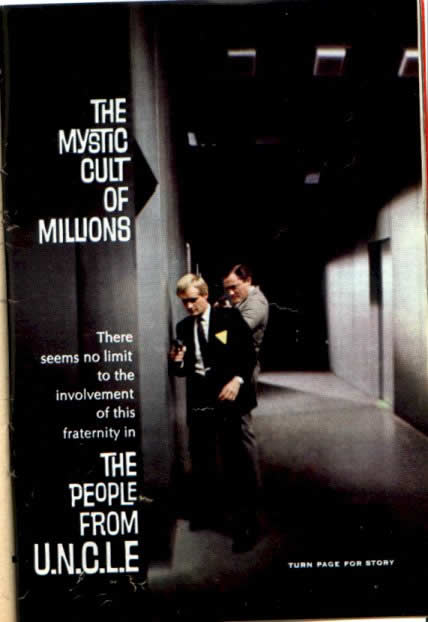

Mystic Cult of MillionsThe People From U.N.C.L.E.

TV Guide March 19-25, 1966

The

Mystic Cult of Millions

The

Mystic Cult of Millions

The People From U.N.C.L.E.

TV Guide March 19-25, 1966

Nothing quite like The Man from U.N.C.L.E. has ever happened to television, not only in program content which has spawned a host of imitators, but in the fact that U.N.C.L.E. almost didn’t make it at all. After a faltering start in 1964, it got a time change and its second wind. Ratings went up and letters began coming in from all sorts of people who had nothing in common except they were U.N.C.L.E. nuts.

Here is a letter from a West Coast college student:

“I do not write fan letters usually but after watching The Man From U.N.C.L.E.

I felt that a letter of appreciation was in order. I feel that your program

offers an escape from our problems. The cast has its problems, but they’re

mostly of a child’s dream world of spies and counterspies.”

A student at the Bronx High School of Science wrote:

“What especially fascinates us is the fantastic array of gimmicks on the

show. These wonderful gadgets are as devious as any apparatus now in our classrooms.

We here at the Bronx High School of Science have developed (on our own time,

of course) quite a few gadgets every bit as sinister as those on your show.

Who in your organization can we contact regarding showing you these for possible

patenting?”

One Monday morning last spring a harassed CBS television producer dictated

this letter to Norman Felton executive producer of The Man from U.N.C.L.E.:

“Without any encouragement from their father, I have reared four wild

Man from U.N.C.L.E. addicts in my own family. Nice children who are, in all

other respects, perfectly normal, they beg be continually, constantly to get

them U.N.C.L.E. cards, THRUSH cards, photos of Robt.Vaughn, the blond kid (Illya?),

etc. Do you have any kits available for fellow producers who must nightly compete

with our superheroes or be branded weaklings in the eyes of their offspring?”

The letter concluded, “Yours desperately.”

Norman Felton, a tall, shaggy sort of man, who looks more like the college teacher he used to be than the Hollywood producer he is, sends out between 50 and 60 thousand U.N.C.L.E. cards every month in response to as many letters which the program receives. He is delighted with the popularity of The Man from U.N.C.L.E.—but with reservations. Until U.N.C.L.E., Felton was identified with serious dramatic programs like Studio One, Robert Montgomery Presents, The U.S. Steel Hour and, more recently, The Eleventh Hour and Mr. Novak. Thus, despite his delight at U.N.C.L.E.’s success, he says, “I would rather have one Novak on the air than six U.N.C.L.E.’s.”

He decided to switch

It was Felton’s long preoccupation with serious TV drama, however, that was responsible for the launching of The Man from U.N.C.L.E. He says, “Three years ago, I decided I wanted to do a series that would be just fun. I ad-libbed a story about a mysterious man who would become involved with ordinary people in adventures with humorous overtones. The concept of the show has never really chanted—we always try to have very human people rather than just the two heroic men. But at first we had to hold back some of the more humorous episodes we made because the network thought it had bought a straight adventure series. It also took the public a while to realize what we were up to. I think that was responsible for our shaky start in 1964. There are still viewers who accept U.N.C.L.E. as straight adventure, which is all right with us.

Concerning the emergence of the unknown “blond kid,” David McCallum, as a star, Felton says, “I never had any idea he would become the hit he has. His part in the pilot film was only a few lines, and he was just one of many actors we considered. We picked him because he looked different.”

A young lady in Los Angeles wrote the following letter to The Man from U.N.C.L.E.: “Does D. McCallum have any toes? If so please send me two pictures of them.”

Thirty-two-year-old David McCallum (no one calls him “Dave”), Scottish son of a musical family, lived for years in cheap flats in London and between 1953 and 1956 appeared in 52 plays a year as a member of a stock company. Now suddenly and unexpected successful, he says, “I’m perfectly happy to receive any symbols that indicate success.” But privately he admits that he is annoyed by some of those symbols—like the David McCallum sandwich in the MGM commissary (sliced chicken and avocado), sensational stories in fan magazines (“David McCallum: Why He’s Taking Special Love Lessons”), and being called “cute” (That’s an American word I hate. A litter of mongrel puppies is cute.”).

And with success has come doubt: “Part of an actor’s metabolism is being insecure. When you get a TV series, you start looking for other places to be insecure.” Last summer during U.N.C.L.E.’s hiatus he made a movie, “Around the World Under the Sea”; but now he says, “If I am working 12 months a year, I wonder if this is the life I want.”

McCallum seems in many ways to be the ultimate actor, but he has little of the actor’s vanity, pretension or self-delusion. In a completely undignified guest appearance on Hullabaloo, he was never once referred to by his own name but always as Illya Kuryakin—at his own suggestion. A year ago, when the character of Illya first began to emerge, he said, “Illya is mysterious. Couldn’t we make Illya and me overlap.”? I’ll be mysterious too.” Thus, he has steadfastly refused to permit picture layouts involving his family—actress Jill Ireland and their three small sons. He says, “An actor’s sole purpose in life is to entertain. If he doesn’t do that, he fails.”

A Kansan mother wrote to the producers of The Man from U.N.C.L.E.: “Our two teen-age sons have pictures of Mr. Vaughn and Mr. McCallum in their room along with those of Barry Goodwater and Dr. Wernher Von Braun.”

No resentment

Robert Vaughn, who has seen The Man from U.N.C.L.E. become, to all

intents and purposes, The Men from U.N.C.L.E., is apparently unperturbed by

the sudden fame of David McCallum, who started out to be his strictly secondary

side-kick and ended up as his co-star (one magazine devoted to the two even

gives McCallum top billing over Vaughn). When it was pointed out that many actors

would be unhappy in such a situation, Vaughn said, “maybe a lot of actors

aren’t as secure as I am.”

The product of a disturbed childhood (“I cried all the time”), Vaughn at 33 is enjoying his fame and all its fringe benefits. He does not object to the Robert Vaughn Sandwich at the MGM commissary (pastrami on pumpernickel with a slice of Bermuda onion), to the fan-magazine stories (“The Two Women in His Life!”), or to the adulation of pubescent admirers. (2000 screaming 12-year-olds in Detroit tearing my clothes off and throwing stuffed animals at me”). He takes time to go into projects he believes important. During the U.N.C.L.E. hiatus, while McCallum was making a movie, Vaughn played “Hamlet,” for free, at the Pasadena Community Playhouse and then returned to the University of Southern California to continue class work for this Ph. D. in the philosophy of communications.

Exceeded fondest hopes

Concerning the impact of The Man from U.N.C.L.E., Vaughn says, “I’m surprised by the reaction—I never anticipated anything like this.” But it is only the magnitude of the reaction that surprises him, not the reaction itself. He insists that he knew all the time that U.N.C.L.E. would be a hit: “I thought so from the beginning and told everybody so. Of course, I began looking red in the face that first January when they were going to cancel us.”

As to the recognition, he says, “I’m not yet Robert Vaughn, only Napoleon Solo. You don’t get to be known as yourself in TV, only in the movies.” And Vaughn wants to be known as Vaughn.

On a plane flying from Los Angeles to New York, Robert Vaughn was handed

the following note from a fellow passenger:

“Mr. Vaughn—May I invade your privacy to say thanks for being so

gracious in giving your autograph the other night. It will be the most exciting

thing we are taking back to our 18-year-old daughter.”

The note was written on the back of one of those unobtrusive brown paper bags the airlines thoughtfully provide for mal d’air.

--Leslie Raddatz