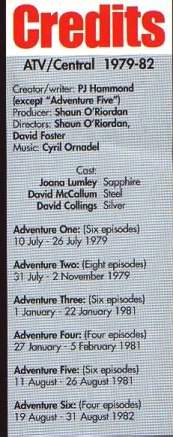

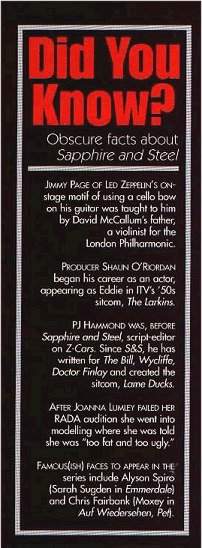

Above

SFX Magazine

The science fiction series that defied you to ask "Well, what was that all about?" is remembered, 20 years on, by Stephen O'Brien

Above

"All irregularities will be handled by the forces controlling each dimension. Transuranic heavy elements may not be used where there is life. Medium atomic weights are available: Gold, Lead, Copper, Jet, Diamond, Radium, Sapphire, Silver and Steel. Sapphire and Steel have been assigned."

So rumbled the God-like voice at the beginning of Sapphire and Steel, announcing the imminent arrival twice-weekly of two inter-dimensional operatives, seconded to Earth to deal with time anomalies, spatial disturbances and bewildered bystanders.

Like Doctor Who, Sapphire and Steel was a peculiarly English expression of science fiction. "I've always been interested in time, particularly the ideas of JB Priestley," reflected series creator PJ Hammond. Indeed, Priestley's plays, An Inspector Calls and Time And The Conways, are perfect templates for the claustrophobic, theatrical and paranoid melodrama of Sapphire and Steel. Even the leads echo Priestley's shadowy protagonist Goole in An Inspector Calls, so resistant was Hammond to illuminate their backgrounds and motivations.

Only six stories were made in the series, all titleless, so

it was up to fans to ascribe them such monikers as "The House",

"The Railway Station", "The Apartment", "The

Photographs", "the Dinner Party" and "The Trap". The

elusiveness of the titles reflected the considered opaqueness of the show

itself, which offers up little information to the lead's backgrounds and in

which the enemy - Time - remains a faceless, ethereal and almost sentient

menace.

Only six stories were made in the series, all titleless, so

it was up to fans to ascribe them such monikers as "The House",

"The Railway Station", "The Apartment", "The

Photographs", "the Dinner Party" and "The Trap". The

elusiveness of the titles reflected the considered opaqueness of the show

itself, which offers up little information to the lead's backgrounds and in

which the enemy - Time - remains a faceless, ethereal and almost sentient

menace.

The sculptor of Sapphire and Steel's seductive, skewed reality was PJ Hammond, who had been dabbling in children's SF on such shows as Ace of Wands and Shadows. He approached Thames with a concept for a new fantasy series for children called Sapphire and Steel in 1977, but the station turned it down. Southern TV were next in line to reject the series before Hammond chanced upon an understanding commissioner at ATV, whose first official decision was to upgrade Sapphire and Steel from a children's to an adult series.

David Reid, Head of Drama at ATV, insisted to producer Shaun O'Riordan that the series required stellar casting. The scripts were sent to ex-Man From UNCLE Ruskie David McCallum and New Avenger Joanna Lumley, both responding with an enthusiastic "yes".

"Shaun rang me and said, 'Guess who we've got?'" recalls Hammond. "They were perfect. They worked closely together to make the characters gel. That was valuable and it was very unselfish on both their parts."

The first story is the only tale that gives away Sapphire and Steel's pre-pubescent origins. When two children's parents disappear, our duo arrive to investigate and irritate and, eventually aided by fellow element Lead (it was Shaun O'Riordan's desire to populate the series with a range of other agents), they discover the disappearance is due to a weakness in Time which was brought about by nursery rhymes being told in certain rooms of the house.

Unlike the other series that exploit the concept of time travel, time in Sapphire and Steel's world is imbued with a sense of malevolent magic, where old objects are held to be dangerous in some way, allowing malignant forces t invade.

The first story also set the template for the rest of the series. The scenario was classic detective fiction. Hammond's delicate marriage of Chandler, Priestley, Agatha Christie and HG Wells spawned an electrifyingly different take on a pretty hackneyed premise. By the end, the status quo is almost always restored, but Sapphire and Steel's savage depiction of spoiled innocence and the vulnerability of decent people to evil give the endings a witheringly bleak quality, which suggests that they can never quite go back to the lives they once had.

Hammond's tales were grandly ambitious, suggesting a scope well beyond the shabby confines of the ATV studios, indulging in metaphysical and philosophical concepts rare in peak-time commercial broadcasting. Remembers David McCallum: "My mother used to have a cleaner, Mrs Puttock, and she saw the first episode and said, 'I loved it, but I didn't understand it', so we always tried to make the stories Puttock-proof."

Even the Puttock factor wasn't enough however for Lumley, who, in mid-scene in one story, broke off in desperation to cry: "For fuck's sake, I can't do this. I don't understand it. I really don't fucking understand it."

Sapphire and Steel are complementary characters, and Hammond was wise enough not to resist the elegant simplicity of the premise. Sapphire, all Chelsea dinner party sophistication and simmering sexuality counterbalances the often awkward and socially brutal Steel and certainly seems the more human of the two, though Hammond denies Lumley's understanding that the characters were alien, stating that they could be best described as "supernatural do-gooders".

"I didn't want to give too much away", says

Hammond, "because once you say where they've come from, you're committed.

We were thinking of doing a story where we introduced the God-like character

behind them, but decided against it".

"I didn't want to give too much away", says

Hammond, "because once you say where they've come from, you're committed.

We were thinking of doing a story where we introduced the God-like character

behind them, but decided against it".

"It was one of those things where the less you explained the more mysterious it gets," suggests Shaun O'Riordan. "I couldn't say we ever knew where Sapphire and Steel came from or where they were going. PJ Hammond could suggest these things and it all worked. None of us completely understood what he was talking about. In fact half the time he said he didn't know where it had come from!"

McCallum, by this time relocated to the UK after more than a decade in the States, enjoyed a good on-set chemistry with Lumley, despite a myriad of differences (McCallum was a fastidious health nut and Lumley was, at the time, a voracious smoker) and on-set rumours of a relationship. "I could never work out if they were having an affair or not," says O'Riordan, "because they used to have breakfast together occasionally. I used to try to get information but I never found out."

The best remembered story remains "The Railway Station", or "Adventure Two" as purists and those at ITC video have it. Part of the reason why this story elicits more late-night conversations than the others is because of its length (it's a confident eight episodes long) and the fact that ITV went on strike a quarter of the way through the story and the channel decided to start showing the entire tale again, rather than simply resume it.

Sapphire and Steel is as minimalist a series as it's possible to get without losing sight of realism. It was always a series that made a virtue out of its three-set shortcomings. Television rarely knows what its strengths are, but Hammond's debts to the drawing room ethos of Wodehouse Christie and Coward meant that theatre and literature cast a longer shadow over Sapphire and Steel than cinema.

Still, the series ventured out with the film cameras for "Adventure Three" (or "The Apartment", for argument's sake), its post poorly-realised segment. Although outside filming is minimal in the story, it compromised the programme's micro-reality and looks severely out of place within the series.

In the story, the pair investigate an invisible penthouse atop a modern-day block of flats which is occupied by two time-travellers from the future, Eldred and Rothwyn, as well as a changeling they've brought with them. Criticisms aside, it does introduce to puckish Silver, played with flirtatious zest by David Collings, who was destined to return for the duo's televisual swansong.

"Adventure Four" ('The Photographs") is another fan-favourite, a tight four-parter oozing stained innocence and omnipresent evil, and boasting a memory-branding villain in The Shape, a faceless being that is present in every photograph ever taken and can pass between them.

PJ Hammond, in a show of dedication perhaps only J Michael Straczynski could match, penned all but six episodes of his TV baby, handling over parenting duties to former Doctor Who scribes Don Houghton and Anthony Read, for the fifth story, subtitled either "Doctor McDee Must Die" or "The Dinner Party" depending on your taste. In this unashamed Agatha Christie pastiche, a wealthy businessman, Lord Mullrine, hosts a '30s theme party in which Time begins to slowly go backwards readying itself to replay a 50-year-old murder.

"I had to take time out for a rest," remembers Hammond. "Therefore Don and Anthony were asked to contribute to the series, but while they used a different approach to the Sapphire and Steel saga by incorporating a 1930s detective story style, it's not a direction I would personally have chosen."

Sapphire and Steel had an erratic TV run, with "Adventure Five" constituting a series in itself. However, the reformation of ATV into Central in 1982, spiralling production costs and the frequent unavailability of the two leads forced the death-knell for Sapphire and Steel.

"Adventure Six" (subtitled "The Trap" in spoiler-insensitive fashion) proved to be the duo's last televised outing. For once, there is no identifiable point of audience identification - everyone of the small cast is an element, though Sapphire and Steel's nemesis, we're told ominously, "answer to a higher authority".

The pair sitting in their respective chairs, just in case

they forgot

Silver returns as back-up once more, but the final story shows Sapphire and Steel more impotent than ever before. The dramatic genius is in establishing their rate within the first minute of the story, imbuing it with a brooding, pessimistic quality that seemed more Play For Today than Rock Follies.

Sapphire and Steel fizzles out with the duo suspended in space and time, the story ending on a chillingly surreal image of the couple looking out from a café window floating in space. Hammond claims this wasn't meant to conclude the series for good. "A further series was though of, but only in a vague sense. During the writing of Story Six, I felt that we had gone as far as we could for the time being. I believed that their fate was to spend a number of Earth years in the trap. This means that they could emerge again whenever the need arises, perhaps being even older."

It was ATV's demise that really ended Sapphire and Steel, through. Typical of the corporate mentality, the new licencees, Central, swept out all but the most blindingly popular of its predecessor's programmes, killing one of the most brilliant science fiction anachronisms of our times. When, post-Star Wars, most of this country's SF jettisoned its English peculiarities, Sapphire and Steel celebrated its island strangeness.

"There is talk, here and there, of the possibility of the series returning," states PJ Hammond. "Unfortunately, those that run the TV companies have been shunning sci-fi and fantasy on a reasonable scale for some time. Should they eventually have a change of heart, who knows? Perhaps we could one day unlock the door of the café that is in nowhere..."

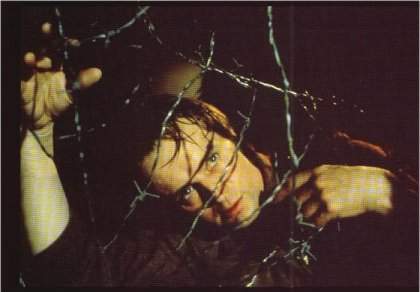

Above: David McCallum often felt a bit of a prick on

Sapphire and

Steel